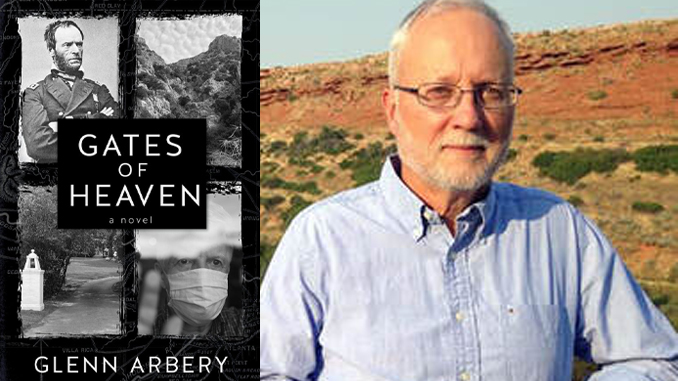

In his most recent novel, Gates of Heaven (2025, Wiseblood Books), Glenn Arbery wraps up the complex, fraught, and evocative chronicle of friends, families, and foes working out their salvation in the contemporary American South and West.

In the trilogy, which began with Bearings and Distances (2015) and Boundaries of Eden (2020), Arbery excavates the American soul and social and cultural landscape in a way few fiction writers today even attempt. The ultimate subject is, of course, not simply the “American” soul, but the human soul. Deeply informed by the resonances of classical myth, history, and the illumination of the wisdom of revelation through a Catholic lens, Arbery’s novels weave astute, unsparing and wry—even hilarious—observation of the absurd and pained ways of human beings, their fraught states of guilt, victimhood and innocence, with, at every sin-tinged turn, a glimmer of hope.

Gates of Heaven is, structurally, the most daring of the novels in the trilogy, which is appropriate considering its setting in the bizarre COVID and election years of 2020-2021. Arbery brings back the characters we’ve gotten to know in the previous books, still carrying burdens from the past into a new era of divisiveness, tribalism, and an unhinged landscape of uncertainty, selective awareness, and helplessness.

In this challenging present, high school student Jacob Guizac confronts an assignment. His father, Walter, has asked his friend, the acerbic academic Braxton Forrest, to supervise a homeschool project for Jacob, which Braxton decides will be a massive report on Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, the man who led the brutal, scorched-earth charge that finally brought the South to its knees. Jacob, whom we know from the previous novel, is a mystic of sorts. He tackles the project and in the process finds himself with a peculiar and powerful gift of connecting with Sherman across time and space, and in his project–as well as his father’s weeks-long COVID-induced coma–past, present, and eternity meet.

In Gates of Heaven, then, Arbery gives us an intricate, probing exploration, in essence, of the consequences of our Original Sin–for individuals, for families, for a nation–and where hope in the fractured mess we are suffering through could possibly lie.

Glenn Arbery recently sat for an interview in his office at Wyoming Catholic College, where he is a humanities professor and former president, on Main Street in Lander, Wyoming.

CWR: You’ve said that when you wrote Bearings and Distances, you did not envision it as the beginning of a trilogy, so how did the trilogy evolve?

Glenn Arbery: Well, the second novel, Boundaries of Eden, really came from the image that became the beginning of the book, which is a boy standing in a field of kudzu. I had to figure out why he was there. I’m being kind of facetious, but not entirely, because really the book came from filling in what might have happened there, which then invoked the action of the previous novel, as it turned out. So some of the characters came over. The main character in the first novel, Braxton Forrest, was more peripheral in Boundaries of Eden, which focused on Walter Peach.

By the time I got to the third one, I really was thinking of it in terms of the characters from the first two. So Gates of Heaven was more deliberately conceived as a kind of conclusion to the trilogy.

CWR: Going back to Boundaries of Eden: did you bring the characters that you brought back because you felt that their story needed to continue, or because it just worked?

Glenn Arbery: I think it’s really because the story needed to continue. Bearings and Distances ended on almost an ominous note, with the revelation of all these sins of the past about to emerge in a new context. So, I see the three novels roughly—and I say this very hesitantly—as a kind of Dantean movement.

The first one’s more infernal, the second one more purgatorial, and at least in glimpses, the third one more paradisal. Though I don’t think anybody reading Gates of Heaven will see it as paradisal.

CWR: Sherman has been an important figure to you for a long time. Did you conceive of writing a Sherman-centered novel apart from these characters, or was he always going to be a part of this story?

Glenn Arbery: I had thought about Sherman back when I was in my twenties. I was thinking that I would write some kind of long poem, something with a kind of an epic feel to it. That never happened, for various reasons.

But Sherman’s always been a kind of antagonist for the native southerner. In this novel, which is set in the COVID year, he emerged as the subject of Jacob Guizac’s project, and then that evolved and took on more and more weight as I wrote the book. Just as it happened to the South in 1864 and 1865, he took over. So the first section of the book is “Sherman Takes Command.”

CWR: My reading of the book sees it as a very organic, natural connection between Sherman and the “present” of the novel, one related to issues of division and destruction and tribalism. Is that how it all came together in your own conception of it?

Glenn Arbery: Yes, that’s the connection.

But he strikes me as a fascinating character on many levels, one being that he was the foster child of Thomas Ewing, who was a very prominent politician in the mid-19th century. He was brought up Catholic in that household after his own father died, but he resisted it the whole time. He’s emblematically modern in the sense that he’s a rationalist; he’s not sure that he doesn’t believe in God, but it’s not a God who would ever give you a vocation.

(Note: Sherman’s son, Thomas Ewing Sherman, became a Jesuit priest.)

He thinks of vocation as a horrible thing. He doesn’t obviously believe in the sacramental understanding that comes through Catholicism. And he touches on various dimensions of American life in the 19th century in ways that reflect his rejection of all these things.

Most people don’t know about Sherman’s career in the American West after the Civil War. He and General Sheridan were in charge of the Indian War, and it was pretty much Sherman’s idea to drive the buffalo to extinction because that would undercut the way of life of the people of the West, a continuation of what went on in the South: you gut the way of life, and the will to fight goes away. So it’s very rational, very effective, in terms of what Machiavelli called the effectual truth. And I don’t know, Sherman just kept emerging through the book, not just in this young man, Jacob Guizac, but also in Jacob’s father, who takes Sherman into his two-month induced coma.

During those COVID years, there was just so much disagreement politically, even among people in the same family. The Biden-Trump election was going on. The nation seemed terribly divided. So the Civil War just seemed to emerge as a kind of parallel, a backdrop against which you judge everything that’s happening now.

CWR: If Gates of Heaven evokes, at some level, the Paradiso, what does the journey there entail? What’s the way out of our brokenness and division?

Glenn Arbery: The way out is hard, especially in the whole southern section of the novel, when Walter and Jacob go back to Stonewall Hill, which is the place that actually survived from the Sherman era.

There’s a lot that has to be rooted out.

If you’re really going to get things right, you have to do this very difficult labor. The most grotesque scenes in the novel is an exorcism, because that’s what it feels like to try to get to wholeness. The way through also involves families loving each other. Marriages staying whole if they can. Sacrifice and goodwill and all those things. It’s the only way through anything, really.

CWR: Between Jacob’s gift of engaging with the past across time and space, and Walter’s visions, which include being judged as Sherman, what I took away was a sense that our division and brokenness is the fruit of a lack of empathy–and Jacob and Walter are both immersed in experiences that express the truth that on a spiritual level, that division can only be made whole by radical empathy and being able to see others–

Glenn Arbery: With love.

It’s possible to see into somebody without love, and in that case, it becomes radically destructive. And I think that’s part of what I’m doing. In those examinations that Walter Peach undergoes in his coma, he’s being asked to answer for Sherman, who is also on trial– but it’s Walter’s soul at stake. There’s some way that we have to answer for each other, even for the person you can’t stand. There’s some way we have to enter into that person and think within their boundaries and try to see some way to open them up and give them access to the redemption being offered if we want redemption ourselves. And I hope that the struggle that Walter had with Sherman is compelling. It was to me in writing.

CWR: Were there other aspects of the book that were difficult to write? And what does that mean as a writer? Is it that you don’t want to confront something, or it’s hard technically?

Glenn Arbery: Some of both, for sure. Sometimes what’s hard is getting your character across the room, as the novelist Caroline Gordon used to say. You have to imagine the details of wherever the character is and who he or she is talking to. That’s a lot of the labor of writing: imagining it sufficiently.

But then there are other dimensions where I feel like I have to open up the areas of the psyche that I don’t really want to address. They are opened up in ways that are profoundly disquieting, but all as a way of getting past them and into some place of grace and real hope. In Gates of Heaven, I’m playing off Dante’s three examinations in Paradiso, on faith, hope, and love. Dante passes with flying colors. But Walter Peach is a little more problematic.

CWR: Another major storyline in Gates of Heaven involves the character of Hermia, whose very existence is due to sinful and even grotesque actions by her progenitors, both recent and distant. In the previous novels, all of this has been revealed to her, and she’s had to learn to live with and even accept her identity. She’s living in Georgia, running a home for pregnant girls and women–in a house that was the locus of some of that terrible history. Tell us about Hermia.

Glenn Arbery: [Her story] echoes things in the Oedipus cycle, because everything that’s most terrible has been done in ignorance. What I’m doing also echoes Faulkner’s novels about the refusal to acknowledge the character and lineage of the black part of the family. But the incest themes also reveal something inturned and self-blinded in the inability to acknowledge wrong and accept responsibility for it. I don’t intend a condemnation of the South, the beautiful South, but an acknowledgement of a centuries-long labor of love and purgation.

So Hermia is trying to work out who she is. She’s the one who has the most to work through, it seems to me, because of who she is. The spiritual journey of Hermia is one of the things that has most occupied me imaginatively. By the time you get to Gates of Heaven, you’re seeing Hermia after her spiritual turn and her conversion. It seems very real to me. I see her as on the way to sainthood.

CWR: What are your thoughts on being a Catholic writer?

Glenn Arbery: When I write scenes that are shocking, it’s because there’s evil that we have to see as such, which makes the good stand out more clearly. Those passages are hard. That’s why I give my narrator of the Sherman sections, Jacob Guizac, a kind of unshakeable innocence. He’s capable of imagining them without being darkly affected by them, because his heart is turned so firmly toward the good. That’s what I hope for my reader.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.