Divorced saints? How can that be? Catholics are more likely to hear edifying stories about pious wives like St. Catherine of Genoa or Elizabeth Canori-Mora, who stayed with wicked husbands until they prayed their erring spouses into repentance. They’re unlikely to hear about cases like St. Godeleva’s where abuse ended in murder. This article will look at saints involved in divorce to show that Catholics in the past had to face challenges of a kind commonly assumed to be modern.

First, a note about the word “divorce”. It comes from the Latin divortium—“a separation,” especially “divorce, the ending of a marriage.” Divortium is the legal term in canon law, from the Middle Ages down to the 1917 Pio-Benedictine Codex Iuris Canonici. Canonists say “decree of nullity” rather than “annulment;” there is no corresponding Latin noun. Some of the cases below cover actual civil divorces terminating marriages. But the medieval dissolutions of marriage cited here—also called divorces—were actually canonical declarations that a marriage never existed. These decrees had both ecclesiastical and civil effect because, in that era, the Church controlled marriage.

The early Church and the first millennium

Our first subject is St. Fabiola (d. 399), a wealthy Roman aristocrat. Girls of her class were typically married off at puberty to much older men. Presumably, this is what happened to Fabiola. Unfortunately, her husband proved so dissolute even by the prevailing double standards for men that Fabiola divorced him. (Despite the triumph of Christianity, Roman law still permitted no-fault divorce on demand by either spouse.) Then Fabiola married a more congenial young man, but he soon died. Repenting of her illicit marriage, Fabiola submitted to a long, humiliating stint of public penance. Once reconciled with the Church, she devoted herself to charitable works, including hands-on service to the sick and poor. Visiting the Holy Land, Fabiola decided not to join the troupe of pious matrons gathered around St. Jerome. She returned to her Roman charities, dying there a decade before the Visigoths sacked the Eternal City.

After barbarian invaders conquered the western half of the Roman Empire, the Church spent the next five centuries evangelizing and re-evangelizing Europe. One delicate issue was persuading newly converted peoples to give up polygamy and divorce2. Although the Franks under Clovis were the first new nation to choose Catholic Christianity in 495, their ruling Merovingian dynasty continued to acquire and discard women at will. St. Radegund (d. 587), fifth of seven wives to Chlotar I, managed to leave her murderous husband and had their union dissolved by taking religious vows. The Church recognized this option as an alternative to divorce.

Christianity was better established by the time the Carolingians replaced the Merovingians in 751. But Charlemagne (d. 814), who does not count as a saint because an antipope canonized him, divorced one wife and kept concubines without censure. For political reasons, the papacy was more relieved than otherwise when the Emperor sent his Lombard spouse away and remarried.

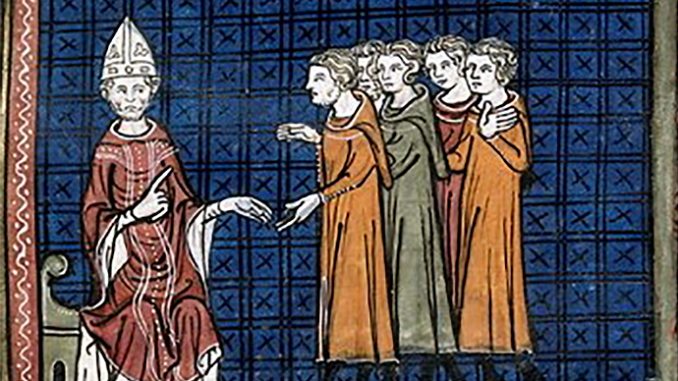

Matters turned out otherwise in 855 when Charlemagne’s great-grandson Lothair II tried to repudiate his new wife, Theutberga, in favor of his old mistress Waldrada. He accused her of incest with her brother, an immoral young abbot, because that sin was an invalidating impediment. Two synods of bishops decided in Lothair’s favor, ordered Teutberga to enter a convent, and allowed his marriage to Waldrada. Theutberga then appealed to St. Nicholas I the Great (d. 867), who was the last powerful pope of the Dark Ages. A dozen years of threats and excommunications followed as Nicholas tried to force Lothair to part with Waldrada. At one point, he commanded Theutberga to remain in the marriage even if this cost her life to defend the principle of indissolubility. Eventually, Lothair yielded to the next pope, was restored to the sacraments, and died in 869. Theutberga survived him by six years.

An era of reform

After the year 1000, the Church’s Age of Lead and Iron gave way to an era of reform. One aspect of this process was greater attention paid to enforcing canon law, including marriage rules. Claiming jurisdiction over all marriages, the papacy found anathema and interdict keen weapons to enforce its will.

But with multiple collections of canons available and no single uniform Code, the simple restrictions against marrying close kin taken from the Book of Leviticus and Roman civil law had gotten entangled with Germanic definitions of kinship, a confusion helped along by forged documents. The degree of consanguinity was now calculated by the number of generations from a common ancestor. Initially, marriage was forbidden with one’s sibling, then with a first cousin, then with a third cousin. But, the eleventh century, the degree of consanguinity was calculated by the number of generations from a common ancestor. Thus, Western Christians were prohibited from marrying their sixth or, to be absolutely sure, their seventh cousins. The principle of affinity barred them from marrying their in-laws within the same seven degrees. (This also applied to comparable connections formed outside of marriage.) But zealous canonists spun the web of restrictions ever tighter: secondary affinity forbade marriage with a spouse’s own in-laws within four degrees; tertiary affinity extended that to the in-laws of those in-laws to the second degree; and quaternary affinity excluded unions with the family of a mother’s first husband or paramour within four degrees.

Although dispensations were possible, the strict application of these onerous rules would have made it almost impossible for anyone to contract a valid marriage. But enforcement was often capricious and generally limited to policing upper-class morals. No one was threatening the marital arrangements of serfs. Churchmen now had the power to interfere with unapproved alliances, while laymen had excuses to dissolve unsatisfactory unions. As we will see, complex restrictions invited abuse.

In about 1051, years before conquering England, William of Normandy raised a storm of controversy by marrying his cousin Matilda of Flanders. Pope St. Leo IX (d. 1054) had forbidden this because they were too closely related. The specific objections are unclear, although William’s uncle, the Archbishop of Rouen, declared: “They shall not riot in a bed of incest.” Normandy was laid under interdict until the Archbishop of Canterbury negotiated a settlement. William and Matilda did penance and donated twin abbeys at Caen, as well as a spare daughter to be the abbess at one of them. Order was restored, and the royal couple enjoyed a happy and surprisingly faithful marriage, becoming the ancestors of every present European monarch.

Leo IX could not keep William and Matilda apart; a later pope, Bl. Eugenius III (d. 1153) could not keep another royal couple together. In 1149, Eugenius had tried to reconcile Louis VII of France and Eleanor of Aquitaine, forbidding their union to be dissolved “under any pretext whatsoever.” Nevertheless, French bishops gave them a divorce three years later for consanguinity in the sixth degree. Eleanor speedily wed her cousin Henry of Anjou—the future Henry II of England—despite being more closely related to him than to Louis. All three parties were descended from twice-divorced Robert II of France, nicknamed “the Pious” (d. 1031).

Further conflicts and challenges

As the twelfth century rolled on and popes grew ever keener to enforce marriage rules, prickly conflicts between canon law and political necessity arose in the Iberian Peninsula. Because the rulers of these small kingdoms could not easily find foreign spouses, they often married within the prohibited degrees. Almost a dozen royal marriages were dissolved in this region, while two others could have been challenged if the papacy had wished.

The most interesting of these cases starts with Theresa of Portugal, who married her first cousin, Alfonso IX of Leon, in 1191. Pope Celestine III objected, but the spouses would not part. They were excommunicated, and Leon was laid under interdict. Five years later, the more powerful Alfonso VIII of Castile pressured the King of Leon to replace Theresa with his daughter Berengaria. The Castilian princess, granddaughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, had previously had an unconsummated marriage to a German prince ended by the Holy See. Theresa left for a convent.

No papal sanctions were employed against Theresa’s sister Malfada, married to Berengaria’s brother Henry I of Castile, who died too young to consummate their union, or to her brother Alfonso II, who was married to Berengaria’s sister Urraca. The latter king’s plans for a major campaign against the Moors seem to have earned him an exemption.

Unfortunately, Rome had not known that the new rulers of Leon were almost as closely related as the previous ones. Newly elected Innocent III, the papal monarch par excellence, ordered this “incestuous” marriage dissolved in 1198, applying the now familiar penalties. Although pleas from Leon’s bishops won a reprieve from his interdict after a year, Innocent scorned the royal children as an “incestuous brood” and proclaimed them illegitimate. In 1204, Berengaria yielded and promised to separate from Alfonso. Money persuaded the pope to reverse himself and legitimize their four children.

But this was not the end of the story. Theresa and Berengaria negotiated an agreement to make the latter’s son king of both Leon and Castile. Theresa’s own daughters were persuaded to become nuns. Ferdinand III, the son who took the united throne, overturned Innocent’s denunciation by becoming a saint as well as the best all-around king to rule in Iberia (d.1252). Theresa (d. 1125), Malhada (d. 1256), and their third sister Sancha (d.1229), who had taken vows rather than wed, were beatified and remain popular in Portugal to this day.

Strange cases and upheaval

Ironically, it was Pope Innocent, a strict canonist who regarded leniency as “detestable weakness,” who cut through the tangle of marriage impediments at Lateran IV in 1215. This Church council reduced both consanguinity and affinity impediments: “let the prohibition of conjugal union be restricted to the fourth degree now and ever after.” All other categories of affinity were abolished.

These sensible rules should have reduced marital disputes; instead, they reversed their polarity. Instead of searching for kinship links to dissolve wedlock, elites sought dispensations to establish it. Sometimes they wed first, rectified later. Little by little, the four-degree barrier was breached.2 In 1412, Thomas of Lancaster, Duke of Clarence, received a papal dispensation—the first of its kind in Church history—to marry his uncle’s widow Margaret Holland, to whom he was related in the second and third degrees of consanguinity and the second degree of affinity. Margaret, by her previous marriage, was to become the great-great-grandmother of King Henry VIII.

Of course, there were still other grounds for seeking divorce, which brings us to an exceptionally cruel and cynical medieval case. To protect his son from a rival line of heirs, the “Spider King” Louis XI of France forced his second cousin, Louis, Duke of Orleans, to marry his daughter Jeanne in 1476. (Their families were hostile: the duke’s grandfather had been murdered for having an affair with the king’s grandmother.) Lame, hunchbacked, and short of stature, Jeanne was judged incapable of bearing children, which proved to be the case. But finding consolation in religion, the princess patiently endured her husband’s harsh treatment. She even saved him from execution after he had rebelled against her brother, who was now ruling France as Charles VIII.

But when Charles died without heirs in 1498, Orleans became King Louis XII and wanted a new, young wife. He sued for divorce, but not on the obvious grounds of consanguinity, which he was curiously unable to document. (He also may have feared that he was not actually his father’s son.) Instead, Louis claimed that their marriage had never been consummated. His disgusting lies appalled Jeanne, who fought against his suit. Nevertheless, the Borgia Pope Alexander VI ruled in favor of Louis on account of defective consent because he said he had been pressured into the marriage with death threats. Louis promptly married Charles’s widow, Anne of Brittany. Following her death in 1514, he wed Henry VIII’s young sister Mary before succumbing three months later.3

Jeanne accepted the pope’s decision, promised to pray for Louis, and retired with the consolation title Duchess of Berry. Already a member of the Third Order of St. Francis, she now had the opportunity to fulfill a lifelong dream by founding a contemplative religious order dedicated to the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Helped by her spiritual director, Jeanne wrote a rule and saw it approved by the same pope who had ended her marriage. She built the monastery and took vows there in 1504, three months before she died. Her order, known as the Annonciades, still exists.

But within a few years, the Reformation overturned the Catholic understanding of marriage. The Reformers, denying that it was a sacrament, transformed it from a religious covenant to a civil contract. Consequently, they allowed divorce in the modern sense for serious cause and permitted remarriage.4 Divorce policy in all Western and Western-derived legal systems derives from these changes, despite Catholic resistance.

Let us end as we began with a civil divorce involving a (future) saint. Joseph—originally Ira—Dutton was born in Vermont in 1846. He served with distinction in the Union Army as a quartermaster and in supervising graves registration. Against the advice of friends, he married Louise Headington in 1866. But as predicted, she proved unfaithful and deserted him a year later. After reconciliation attempts failed, he drank heavily until 1876. He divorced her in 1881 but felt called to do penance for his “lost decade.”

Ira entered the Catholic Church in 1883 and took the name Joseph in honor of his favorite saint. After testing a vocation with the Trappists of Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky for twenty months, he made his way to Hawaii in 1886 to assist St. Damien Veuster at the leper colony on Molokai. St. Damien had already contracted the leprosy that would kill him in 1889. Refusing any compensation, Joseph managed the men’s part of the colony for the next 44 years while St. Marianne Cope and her nuns served the women after 1890. They transformed the settlement into model care facilities.

Admirers worldwide mourned Joseph’s death in a Honolulu hospital on March 27, 1931. The diocesan cause for his canonization opened in 2022 and sent its documentation to Rome in 2024. This “brother to everybody” has been officially proclaimed a Servant of God.

Regrettable patterns, important lessons

In conclusion, what can we learn from these examples? One regrettable pattern is the capricious and politically motivated intrusion by ecclesiastics. While laying heavier and heavier burdens on laymen, they eased them only sometimes in specially favored cases. (Compare complaints today about laxity in American marriage tribunals.) The Church’s canon laws on marriage are much simpler these days. But it is still essential that they remain theologically sound, clearly expressed, and justly enforced.

Although spouses in times past may not have expected the same degree of emotional fulfillment in marriage as we do, marital failure still hurts. Whether divortium meant divorce or annulment, families were disrupted, spouses were humiliated, and children lost contact with parents—the same kinds of tragedies seen today. The saints profiled here—Fabiola, Radegund, Theresa, Ferdinand, Jeanne, and Joseph—refused to see themselves as doomed, much less damned. Instead, they turned their predicament into an opportunity to serve others. That is a lesson for everyone in every state of life, whether divorced, widowed, married, single, or in religious vows.

Endnotes:

1 Although only Western cases are considered here, St. Vladimir/Volodymyr of Kiev/Kyiv (d.1015) is a dramatic example of this. Upon conversion, he dismissed his five wives and numerous concubines, was rewarded with the hand of a Byzantine princess, and became of ancestor of many later royals, including the present King of England.

2 In 1361, Edward the Black Prince of England wed his too-close cousin Joan the Fair Maid of Kent before buying a papal dispensation to regularize it. A French nobleman’s request to marry his brother’s widow had been denied in 1392, but another was permitted to wed his deceased wife’s sister in 1417.

3 Mary’s next husband, Charles Brandon, had also been through a questionable divorce. Did knowledge of his brother-in-law’s experience subliminally influence Henry VII? Was it a condign punishment that the blood of all four men mentioned in this section soon went extinct in the male line?

3Although Henry VIII’s marital escapades (and their cost to saints) are too well known to examine here, he actually shed his first and fourth wives by annulment rather than legal divorce.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.