While Christopher Columbus was crossing the Atlantic Ocean and discovering the New World for Spain, Portuguese explorers were traveling the other way around the globe. That is how they discovered a trade route—and the ancient cultures of the Asian continent—in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

Soon afterward, Catholic missionaries began traveling to Asia to bring those peoples the Good News. Some Catholic priests discovered the kingdom of Vietnam.

Vietnam had been governed by imperial dynasties for many centuries before Europeans arrived. The Vietnamese people largely practiced ancestral worship, although some followed Buddhism, Taoism, and Islam. Confucianism tended to dominate Vietnamese culture, and some aspects of that philosophy apparently made it easier for the Vietnamese to accept Christian beliefs. By the early sixteenth century, there are records of a government edict which prohibited Christianity, indicating that the Vietnamese had not only been evangelized but that many had embraced Catholicism.

The geography of modern Vietnam is somewhat unusual. It is largely bounded by mountain ranges, rivers, and a sea, creating an unusual S-shape. Vietnam is about 1000 miles long and 30 miles wide at its narrowest point. As a long, narrow country, its geography has sometimes protected it from its neighbors, Cambodia, China, and Laos. But sometimes not.

Throughout the seventeenth century, missionaries from the Dominican and Jesuit orders evangelized Vietnam, as did French priests from the Paris Foreign Missions Society. These missionaries developed a Vietnamese alphabet, wrote dictionaries and catechisms, established seminaries to educate and ordain Vietnamese priests, and founded a religious order for women. Although it was still mission territory, the Church in Vietnam continued to grow, and bishops were appointed.

On the other hand, government authorities—in Vietnam and other Asian countries—were often suspicious of all things European. Quite reasonably, they were concerned about the effect of Christianity on their native culture. They also worried that Spanish and French priests were secretly working as spies for their governments. Those concerns repeatedly metastasized into violent persecution throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

Blessed Andrew the Catechist was the first Vietnamese to be recognized as a Catholic martyr. Andrew served as a lay catechist for the French Jesuit priest, Alexandre de Rhodes. De Rhodes was already in prison when soldiers showed up to arrest an elderly catechist, and when they found nineteen-year-old Andrew, they arrested him instead. The local mandarin tried to make Andrew renounce his Christian faith, but when Andrew refused, the mandarin ordered Andrew to be executed the next day. A large crowd showed up for the execution, and Andrew encouraged the Christians present to remain faithful and called upon the name of Jesus before he was beheaded.

Over the next three centuries, it’s estimated that 130,000 Catholics died as martyrs in Vietnam. Vietnamese authorities issued decrees that made the practice of the Catholic faith illegal, and they forced foreign missionaries into exile. (Fr. Alexandre de Rhodes, for example, was taken out of prison and forced to leave the country. He was never allowed to return to Vietnam, and he died on mission in Iran.) Waves of persecution continued for decades on end. Christians were brutally executed by beheading, by suffocation, and by being flayed alive.

The Church recognizes 117 of these Vietnamese martyrs on November 24. These 116 men and one woman died during the years 1745 to 1886. They include eight bishops, sixty priests, many laymen, a seminarian, a teenager, and a grandmother.

The most famous of these martyrs is Saint Andrew Dung Lac (1795-1839), who grew up in a poor family, became a priest, and served the faithful in secret when the practice of the faith was outlawed. He was arrested twice for being a priest but was released each time because the faithful paid his ransom. Andrew tried to hide from the authorities and moved to another region. However, he continued to serve as a priest, and he was arrested a third time, tortured, and executed by beheading.

Another martyr, Saint Jean-Théophane Vénard (1829-1861), was a French missionary who was also arrested during a period of persecution. When he refused to renounce his faith, he was, like many other priests, imprisoned in a tiny cage. Many Catholics died in these cages. Yet from this humiliating prison, Théophane wrote letters to his family which were full of trust in God. These letters made it back to France and inspired many Frenchmen, including the young Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. Théophane also died by beheading.

The authorities executed many lay Catholics, but not all of them. Instead, the authorities tortured faithful Christians through almost diabolical methods while in prison. When these Christians were released, they were often deprived of all their possessions. Some Christians were tattooed with the words “false religion” on their faces. Entire villages of Christians were simply destroyed.

Not all the recorded Vietnamese martyrs have been granted the title of saint yet. Some have been declared Servants of God, including groups of Jesuit priests and laymen who died in outbreaks of persecution in the years 1723 and 1737. During the period 1858-1862, more diocesan priests, religious sisters, laymen, and laywomen died as martyrs and have also been declared Servants of God.

Most of us have never heard of Minh Mang or Tu Duc, two Vietnamese emperors who initiated widespread persecutions of Christians in the nineteenth century. But almost everyone has heard of the Vietnam War, Saigon, and communist prisons.

Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan (1928-2002) was born into an educated, cultured family in Vietnam. His grandfather had served as a counselor to a Vietnamese emperor, and Francis later said he could name his Catholic ancestors, including some martyrs, all the way back to the seventeenth century.

Francis’ family was also deeply Catholic. According to Francis’ sister, “Almost every day, my mother would say to us: ‘When you are in lessons or playing on the playground, never forget that you live in the presence of God.’”1 Francis was a devout boy and recognized a call to the priesthood as a teenager. His seminary classmates later commented on his sense of humor, his intelligence, and his prayerfulness. He was an excellent student and was ordained a priest in 1953.

After a few years, he was sent to study canon law in Rome, where he graduated summa cum laude. Back in Vietnam, he served as a professor, rector, and vicar general. He was the first Vietnamese to be appointed bishop of the city of Nha Trang, and he doubled the number of seminarians, encouraged new lay movements, and held important positions within the South Vietnamese bishops’ conference. Pope Paul VI named him coadjutor archbishop of Saigon on April 24, 1975, but six days later, the city of Saigon was conquered by the North Vietnamese Army.

To the new communist leaders ruling Saigon (now called Ho Chi Minh City), Francis’ appointment must have seemed like a disaster waiting to happen. It was bad enough that he was a Catholic archbishop who had lived in Rome. But Francis’ uncle was none other than Ngo Dinh Diem, the Catholic president of South Vietnam from 1955 to 1963.

As Geoffrey Shaw explains it, “Diem, his family, and his regime were far from perfect, but he was a rare man in South Vietnam at that time: a genuine, traditional, nationalistic Vietnamese leader with political legitimacy.”2 Diem’s presidency was initially supported by the US government, but for complicated and now discredited reasons, the CIA secretly supported a coup, which directly led to Diem’s assassination. The history of Vietnam and the world could have been very different if Diem’s murder had not occurred.

On August 15, 1975, the Solemnity of the Assumption, Francis was arrested by the communist government. He was tortured, starved, humiliated, and placed in a small, windowless, leaky cell. Of the thirteen years he was imprisoned in Vietnamese communist prisons, nine were spent in almost complete silence and isolation in solitary confinement.

Under such inhumane conditions, it would have been easy for him to give up his faith, become bitter, or even have a mental breakdown. One day, when he was struggling to pray and mourning his inability to care for his suffering flock, he heard the words in his mind, “There is God’s work, and then there is God.”3 As one biographer described it:

It was a moment of transforming revelation. Thuan pictured Jesus crucified and understood that when Jesus was most helpless, his arms and legs nailed to the cross and life draining out of his body, it was then that he accomplished the most for humanity. At his weakest moment, Jesus redeemed the world.4

Now armed only with an acceptance of his own weakness, Francis’ love for Jesus Christ deepened, and his soul was purified. By God’s grace, he was at peace in a prison cell. He was able to write short prayers on the pages of a calendar, which were smuggled out of prison and published to encourage faithful Catholics. Using his hand as a chalice to hold a few drops of wine, he celebrated the Mass solely from memory. He forgave his tormentors and treated his guards with such kindness that some of them converted to Christianity and became his friends.

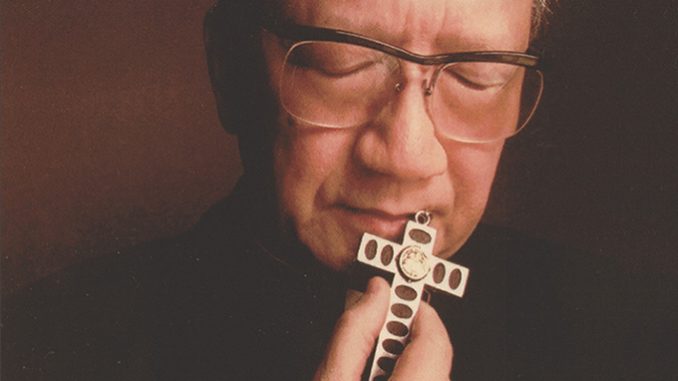

Whether it was due to the end of the Cold War or due to Francis’ inexplicable influence on prison guards, Vietnamese authorities allowed him to leave the prison in 1988, although under house arrest. In 1991, he was allowed to visit Rome, but he was warned that he would not be allowed to return to Vietnam. Living in Europe, Francis was appointed to various important posts, was named a cardinal in 2001, and died of cancer in 2002.

Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan has been declared a Servant of God, and his writings were later published as books: The Road of Hope and Five Loaves and Two Fish. A website was recently launched to teach more people about this brave, gentle man and to promote his cause for canonization. Many Vietnamese Catholics, both those still living under communist rule in Vietnam and those who fled to freedom, remain devoted to their Christlike bishop.

What gave so many Vietnamese Catholics and saints the strength to face persecution and death? God’s grace, of course. And as Servant of God Francis explained it, in words that apply to Catholics suffering anywhere in the world, whether in the past, present, or future:

If you lack everything or have lost everything but still have the Blessed Sacrament, you in fact still have everything, because you have the Lord of Heaven present on earth.5

Endnotes:

3 Andre Nguyen Van Chau, The Miracle of Hope, Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan, Political Prisoner, Prophet of Peace (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 2003), 207.

5 Archbishop F. X. Nguyen Van Thuan, The Road of Hope (Federation of Vietnamese Catholics in the USA), no. 363, p. 113.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.