Does Saint Patrick pray for Ireland and the Irish from Heaven? Does Saint Frances Cabrini still care about the difficulties faced by residents of Italy, her native country, or by the citizens of America, where she became a naturalized citizen?

The saints, of course, have already entered “into the glory of Christ and into the joy of the Trinitarian life,”1 as it says in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. But the Catechism also reminds us that “the blessed continue joyfully to fulfill God’s will in relation to other men and to all creation.”2 The men, women, and children who have received the beatific vision of God do not become amnesiacs, forgetting about their loved ones, their friends, and their native countries when they enter Heaven. By God’s grace, they pray for us.

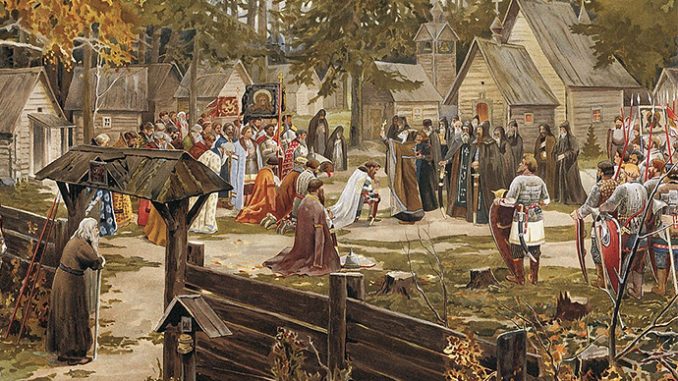

The saints of Russia pray for Russians, too, but Westerners’ knowledge of Russian history tends to be sketchy. A review of the lives of some holy Russians can help us to understand the history of Christianity in Russia itself.

According to some traditions, the Apostle Saint Andrew spread the Gospel in the modern countries of Greece and Turkey before he traveled to Ukraine. Whether Saint Andrew erected a cross in the city of Kiev, as is traditionally believed, is debatable, but missionaries certainly began to evangelize the pagan Slavic peoples by the ninth century. Most famously, Cyril and Methodius (recognized as saints by the Catholic Church) were sent by Patriarch Photius I of Constantinople (recognized as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church). They and other missionaries gradually converted people to Christianity throughout Great Moravia, a region also including portions of modern Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine.

Saints Cyril and Methodius died in the late ninth century, and Saint Olga (879-969), princess of Kiev, became a Christian about a century later. Unfortunately, her conversion—and the pressure she exerted on her citizens to do likewise—did not lead to widespread conversions.

But King Vladimir the Great of Kiev (c. 958-1015), also a saint, chose baptism in 988, for reasons that were both spiritual and political. He decided to allow missionaries from Byzantine Constantinople to enter his kingdom and married a Byzantine princess. He also built churches and destroyed pagan monuments.

Following the Great East-West Schism of 1054, the peoples of Western Europe generally followed Rome, while the people of Russia, among others, retained their ties to Constantinople. The importance of the Church in Russia increased when Constantinople (and the Byzantine Empire) fell apart in 1453. The Russian Orthodox Church thus (according to some) began to see itself as the “Third Rome,” that is, the imperial successor to both the Roman empire and the Byzantine empire. The resulting tension over the status of the Russian Orthodox Church with respect to the status of the Catholic Church has created problems for centuries.

At present, both the Russian Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church have their own canonization processes and lists of saints. When the day finally comes for reunion between these “two lungs” of the Church3—and may that day come soon, by God’s grace—then we can worry about reconciling our liturgical calendars (and many other things).

In the meantime, the Catholic Church took a step toward acknowledging the holiness of medieval Russian Christians when it added two Russian saints to its liturgical calendar in 1940: Abbot Saint Sergius of Radonezh (1314-1392) and Bishop Saint Stephen of Perm (d. 1396). Blessed Leonid Feodorov (1879-1935), the exarch of Eastern Catholics in Russia, was also added to the Catholic calendar in 2001.

While followers of Jesus Christ may be divided in this world, they are not divided in the next. Any monks and abbots, nuns and abbesses, bishops and patriarchs, children and adults, martyrs and missionaries from Russia who enjoy the beatific vision are surely praying for the Russian people from Heaven. Since it is estimated that Communism caused the deaths of twenty million Russians4 during the seven decades of Communist rule, it is reasonable to assume that some—perhaps many—of that incomprehensibly large number died as martyrs because of their faith in Jesus Christ.

After all, although the Orthodox Churches are separated from the Catholic Church, the Catechism of the Catholic Church reminds us that our communion with those churches “is so profound ‘that it lacks little to attain the fullness that would permit a common celebration of the Lord’s Eucharist.’”5

The exact number of Russian Orthodox saints and martyrs under Communism is a matter for that Church to settle. But we Catholics have some idea of the number of Russian Catholic martyrs. In 2002, the Conference of Catholic Bishops for the Russian Federation collected the biographies of 1,800 heroic and holy Catholic clergy and laity. These men, women, and children suffered under Communist repression in the USSR during the period of 1918 to 1953. The bishops declared sixteen of those inspirational Russian Catholics to be Servants of God.

One of those sixteen, Anna Ivanovna Abrikosova (1882-1936), was born into a noble family in Moscow. Well-educated and highly intelligent, she married a cousin, Vladimir Vladimirovich Abrikosov. After a period of searching, both decided to leave the Russian Orthodox Church and enter the Catholic Church. Vladimir became a priest, while Anna became a Dominican tertiary and took the name of Mother Catherine of Siena. Vladimir and Anna, who loved each other deeply, then chose to live as brother and sister. As the Communists increased their persecution of Christians in Russia, Fr. Vladimir was expelled, while Mother Catherine refused to leave her spiritual daughters and was imprisoned. Her loving, Christlike witness continued to inspire her sisters, as well as other prisoners (including prostitutes and thieves), and she probably died in solitary confinement after undergoing surgery for breast cancer in 1936. Details about her life can be found here, and biographies of all sixteen Russian Servants of God can be found here and here.

While we can be grateful that the brutality of Communist rule has ended in Russia, the situation of the Russian people today is hardly idyllic. That’s why we Western Christians should join the Russian saints in Heaven as they pray for the Russian people—and for more than just an end to the war in Ukraine. After all, for seventy-two years, Catholics all over the world prayed the rosary not for the conquest of Russia but for the conversion of Russia to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Our Blessed Mother, the Lady of Fatima, the Mother of God—she is loved by many titles—would remind us that we all need to pray and do penance for our personal sins, as well as the sins of our nation, and she would surely want us to keep praying for the Russian people. In the end, there is only one true empire worth joining: the Kingdom of God.

Endnotes:

1 Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 1721.

2 CCC, no. 1029.

4 Stéphane Courtois et al, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999), 4.

5 CCC, no. 838, quoting a discourse by Pope Paul VI, December 14, 1975. See CCC, nos. 832-848 for more detail on this thorny issue.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.