For nearly thirty years, those interested in learning about the vast and complex history of the Catholic Church’s liturgy have had recourse to Marcel Metzger’s History of the Liturgy: The Major Stages. Translated from the French by Madeline Beaumont and issued in a reasonably priced softcover edition in 1997, an updated and expanded edition of this classic work was published in May 2025 by Liturgical Press. It is a solid work: informative and thorough, if somewhat prosaic and academic in approach, offering a perfectly satisfactory historical foundation to the study of the Catholic liturgy.

Now, however, a new work by Cosima Clara Gillhammer, titled Light on Darkness: The Untold Story of the Liturgy, offers an alternative—and compelling—approach.

In her introduction, Gillhammer notes that her book is meant for a wide audience: not just Christians, but anyone who wants to understand how the Catholic liturgy has profoundly shaped Western culture. As such, she offers a concise description of essential Christian beliefs based upon the Apostles’ Creed, which will be useful to those who are not already familiar with Christian beliefs. Gillhammer also provides a clear methodology, describing how she will approach her topic: she focuses primarily (although not exclusively) on the Roman Rite of Catholicism, she situates it within a Western context, and she does so in an approachable narrative style.

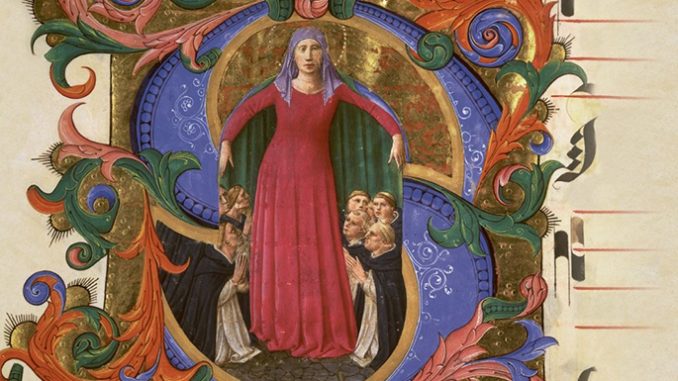

Gillhammer admits that her approach sometimes requires poetic license derived from the available information. For example, the first chapter begins with a compelling description of the creation of an illuminated capital in the Ormesby Psalter. For this narration, Gillhammer obviously cannot rely upon a first-hand account of precisely how the scribe or scribes created the letter on the page, but it does not require wild leaps of conjecture to describe the process, since it is generally well understood. Thus, Gillhammer can provide a compelling account of the craftsmanship and dedication that were required to create the beautiful image of King David playing his harp (printed in color, as one of the many fine illustrations in the text). And, more importantly, she contextualises the artistry not only within its biblical significance but also within the cultural context contemporary to the creation of the illuminated manuscript itself.

Paired with her narrative depictions of religious life, Gillhammer’s effort to explain the cultural positioning of the liturgy and the creation of works like the Ormesby Psalter recommends her approach to the study of the liturgy. The reader is treated to believable vignettes that show the immense importance of the liturgy in the ordinary lives of the faithful. And that importance is explicated through an examination of the texts and practices that run alongside liturgical practices and developments.

In the case of the Ormesby illustration of King David, Gillhammer notes that the image itself is not unique: it is a reference to the biblical association of King David with the Psalms. The Psalms themselves featured (and still do feature) prominently in the religious life of ordinary people, who recite them as prayers within the context of the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours.

Thus, recitation of Hebrew poetry is transformed into an act of prayer: the reader becomes a supplicant for whom the meaning of the verse is personal rather than historical. When the reader says, “Have mercy upon me, O God, after thy great goodness,” it is not merely an echo of King David’s guilty lament after his betrayal of Uriah, but also an evocation of the speaker’s own plea for mercy. As Gillhammer observes,

What happens through the praying of the penitential psalm by a community of worshipers in a church is that which is characteristic of liturgy more broadly: in the moment of liturgical performance, the congregation inhabits the text. The words of the psalm are made relevant to the present reality of the lives of the congregation. The ‘I’ of the psalm is no longer primarily the voice of the psalmist or King David himself, but it becomes the ‘I’ of every individual worshipper.

In this way, what is experienced in the context of the liturgy can become an important aspect of personal devotion beyond the liturgy itself, touching upon scripture, art, and acts of piety.

These observations about how the liturgy and liturgical modes of devotion function in the lives of believers are accompanied by narrative exposition, imagining how those practices might have been lived and experienced in medieval settings. For example, in the passage immediately following the explanation above, Gillhammer imagines the recitation of the Psalms in choir:

In the early hours of the morning, we enter a dark church to sing Lauds, the morning office. The sky outside is still dark, only a golden hue on the eastern horizon and a chorus of birds announcing the coming of dawn. The church is dimly illuminated by candles in the choir stalls; not enough light to give a clear sense of the size of the building, only an awareness of great vaults and slanting columns above. it is cold inside, and the air smells of candle wax and incense. It is cold inside, and the air smells of candlewax and incense. The office begins … Psalm versus are sung, alternating between the sides of the choir. One side calls, the other responds, echoing and continuing each other’s thoughts as the psalm moves from confession of sin to hope of renewal in God’s mercy. … As the office progresses, the sky outside grows gradually lighter, dispelling the shadows inside the church. First rays of sunlight fall through the high, arched windows to the east, colourful reflections of the stained glass illuminating the altar as the final verse of the song speaks of God’s merciful acceptance of offerings.

Gillhammer precedes this narration with the words, “Let us for a moment imagine,” and indeed this scene is an example of the type of poetic license that Gillhammer indicated she would employ. But ‘imagined’ and ‘fictional’ are not perfect equivalents. The imagined scene that she provides is firmly grounded in reality, not fantasy, and what it portrays must surely have happened countless times over many centuries in the life of the medieval Church.

Although Gillhammer makes a point of explaining that Light on Darkness is not intended as an academic study, her work is robustly supported and has been published through the University of Chicago Press. Many of her references are available through open-access sources for those who are interested in further reading. And, in a move deserving of praise, she has developed a website that includes audio recordings of all the music discussed in her book alongside the more traditional media resources and references for her text. This resource is particularly important given that the book is intended even for those who are unfamiliar with Christian practices and art. Art may be reprinted on the page, but music is ill-served by a treatment in words alone, even amongst those who have a solid grounding in music performance and theory, to say nothing of those who are unfamiliar with it.

Nonetheless, Gillhammer modestly insists that her work does not aspire to be a definitive historical study of the chronological development of the liturgy. Instead, she adopts a thematic examination of the liturgy in chapters with titles such as “Love,” “Hope”, “Grief,” and “Death.” An examination of her method in one of these chapters will help to illustrate the approach she takes across the volume.

In Chapter 5 (“Grief”), Gillhammer begins with an overview of the texts used in the liturgy on Good Friday. From this, she moves to a presentation and discussion of the Stabat Mater dolorosa, a poem originally written in 13th century Italy and added on an ad hoc basis into regional liturgies, before being suppressed on the grounds of unifying liturgical practises by the council of Trent (1545–1563), and then restored (as part of the Feast of the Seven Dolours of the Blessed Virgin Mary) in 1727. After considering how grieving parents may find in the Stabat Mater an emotional evocation of their own experiences of child loss, Gillhammer moves from the intimately personal realm of private grief to public expressions of the content of the Stabat Mater. She considers other texts, paintings, and sculptures, including, inter alia, the 14th century poem “Stone wel, Moder, vnder rode,” Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, and Michelangelo’s Pietà, before concluding the chapter with modern sculptures, films, and graphic novels. The result is a chapter—one of ten like it, not counting the introduction and conclusion—which admirably demonstrates how cultural practices reflect and respond to the theological and emotional content of the liturgy.

Light on Darkness is not merely informative; it is, in some ways, transformative. In the days that have followed the arrival of this book, this reviewer has found himself reflecting upon the liturgy he experiences in his own local Catholic parish, thinking and meditating on its presence and influence. And within the book itself, the inclusion of full devotional texts (side-by-side in translation), many color illustrations of inspired works of art, and moving narrations of devotional experiences come together to yield work that is both instructive and prayerful.

What critiques might be offered are scarce and minor. The illustrations would have benefited from being provided on glossy plates instead of being color printed on the standard paper of the page. This would have yielded higher quality images with better detail and brighter colors, but it would also have significantly added to the cost of the book, which is very reasonably priced even in hardcover. And there are places where there could have been a little more historical contextualisation and discussion of liturgical development. Even if that is not avowedly the central purpose of the text, there are places where some small discussion of that sort would not be unwelcome. But this is more a matter of taste and the satisfaction of personal interest than any sort of genuine critique.

In the end, Gillhammer’s Light on Darkness is a thoughtful, reflective work with much to commend it to those who want to understand the major role in Western cultural formation that has been (and still is) played by the rites and practices of the Christian religion. But even those who are devout Christians will come away from Gillhammer’s text with a renewed appreciation for the beauty and importance of the liturgy—a Christian birthright worth cherishing and preserving so that it may continue to inspire for centuries and millennia to come.

Light on Darkness: The Untold Story of the Liturgy

By Cosima Clara Gillhammer

London: Reaktion Books (University of Chicago Press), 2025

Hardcover/eBook, 256 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.