I have long been proud of my kids for having spontaneously decided, many years ago, to give up all video games every Lent, except on Sunday afternoons and on any solemnities. Carlo Acutis, though, was next level. At eight years old, he was given a PlayStation console — and he resolved to limit himself to one hour a week. “The GOAT,” as my kids approvingly say.

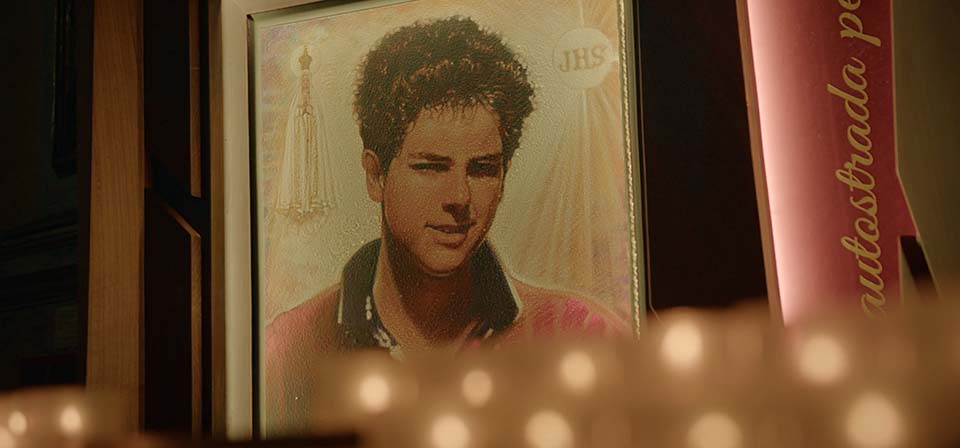

Blessed Carlo Acutis — soon to be the first Millennial saint — died at age 15 in 2006. Carlo Acutis: Roadmap to Reality, from documentarian Tim Moriarty (Jesus Thirsts), weaves together three narrative strands. There are standard biographical elements featuring interviews with Carlos’s family and loved ones as well as talking-head commentary over archival images and dramatized segments. We also follow students of North Dakota Catholic high schools on an Italian pilgrimage organized by Bismarck’s University of Mary, with destinations including Milan, Carlo’s hometown, and Assisi, where his body is displayed in a glass tomb at the Shrine of the Renunciation. Finally, linking the first two, and providing much of the sense of topical urgency, is an indictment of the dark side of the digital revolution and its social, psychological, and spiritual implications.

For the filmmakers, the essentially disembodied quality of digital experience is fundamental to the threat it poses to real-world wellbeing… This is the antithesis, the filmmakers argue, of the corporeality of holy communion.

To build their case that the ubiquity of digital media, and the many hours a day that young people devote to it, is a multifaceted crisis — not only a mental health threat and a social concern, but also ultimately a spiritual danger — the filmmakers turn to commentators of various stripes. Some are clergy, including University of Mary president Msgr. James Shea and National Eucharistic Congress chair Bishop Andrew Cozzens of Crookston, Minnesota. Others, such as Chris Stefanick and Rod Dreher, are popular religious writers. Still others are academics, including Harvard neuroscience researcher Sophia Carozza, John Paul II Institute philosopher D.C. Schindler, Duquesne ethicist John P. Slattery, and Timothy O’Malley, director of Notre Dame’s McGrath Institute for Church Life.

The film’s case is that Carlo is quintessentially a saint for our troubled times, for at least two reasons. First is his moderation regarding digital media, a salutary example to screen-addicted young people (and older people). Over the days of the pilgrimage, as we see the students emerge from withdrawal from the phones left behind, they begin to connect with one another in new ways — “becoming more human as they become less digital,” in the words of one commentator. Toward the end there is even some unease about returning to their phones.

Second is the specifically Eucharistic dimension of Carlo’s spiritual life as well as his web development efforts. While the most famous of Carlo’s websites focuses on extraordinary Eucharistic miracles such as bleeding hosts, more important is Carlo’s commitment to daily Mass and Eucharistic adoration.

In an inspired choice, the film dramatizes its critique with Apple’s roundly pilloried 2024 “Crush!” advertisement for the iPad Pro.

For the filmmakers, the essentially disembodied quality of digital experience is fundamental to the threat it poses to real-world wellbeing. The infinite plasticity of digital reality — a realm that can become whatever we want, in which we can become whatever we want — can be seductive, reshaping our sense of self and how we relate to the world and to one another. This is the antithesis, the filmmakers argue, of the corporeality of holy communion: the bodily reception of the flesh and blood of God incarnate, uniting us mystically not only with Christ, but also with one another. The Eucharist, the Mass, is thus proposed as the ultimate antidote to digital unreality and isolation.

In an inspired choice, the film dramatizes its critique with Apple’s roundly pilloried 2024 “Crush!” advertisement for the iPad Pro. With typical Apple bravado but shocking tone-deafness, this ad placed an assortment of musical instruments, art supplies, electronic devices, and other artifacts in a hydraulic press and proceeded to slowly, relentlessly demolish them, symbolically replacing the wreckage with an iPad Pro. The effective message: The world no longer needs physical trumpets and pianos, paints and clay, arcade games, plush toys, or perhaps much of anything at all; you can do it all, live your entire life, on a screen. (Is it worth noting that the ad’s failure and Apple’s apology suggest that the worst pitfalls of the digital revolution still face significant mainstream resistance?)

We never know the far-reaching effects of the good (or the evil) that we do to others. Kindness and care — or their absence — can change the world, for good or for ill.

At times it may be unclear to what extent the contributors are or aren’t on the same page. In exploring the historical roots of technological revolution, the filmmakers look at the emergence both of modern science in the 16th century and of digital technology in the 20th. Schindler, Dreher, and Slattery appear to interpret the birth of science fundamentally as a break with the sacramental medieval worldview and the advent of a control-based approach to nature. Dreher, in particular, paints a dark view of the scientific revolution, emphasizing its kinship to alchemy and Francis Bacon’s alleged philosophy of “torturing nature to make her give up her secrets” (an interpretation of Bacon disputed, incidentally, by many scholars).

No one here links the birth of modern science to the Christian worldview, as historians of science have done (see, e.g., Thomas Woods’s How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization). Crucially, McGrath and Carozza do emphasize the positive contributions of modern science, with Carozza in particular highlighting with precision that it is when the scientific method becomes “the dominant, exclusive way of relating to the world” that problems arise.

In my review of Jesus Thirsts I noted that I wished the film had developed the relationship between the Eucharist and active concern for the poor. Carlo Acutis fleetingly describes Carlo as “a great friend of the poor and downtrodden of society,” but omits specific anecdotes about Carlo, for example, volunteering at a soup kitchen and buying a sleeping bag for a homeless man. Whatever role corporal works of mercy and Catholic social teaching may play in the antidote to digital disembodiment, they aren’t explored here.

Carlo Acutis does underscore the edifying effects that Carlo had on his initially nonobservant parents and on a Hindu man, Rajesh Mohur, hired to help care for Carlos, whom Carlos helped to lead to Catholic faith and baptism. Just as importantly, we see the debt owed by Carlos, and therefore the world, to the Polish nanny of his youngest years, Beata Sperczynska, his first instructor in the faith. We never know the far-reaching effects of the good (or the evil) that we do to others. Kindness and care — or their absence — can change the world, for good or for ill. Perhaps this is the most important message of Carlo Acutis’s life, and of this documentary.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.